A Short History of Fort Parker

On a bright May morning in 1863 Bill Fairweather and his party found gold near Virginia City Montana. They must have interpreted the find as a just reward after having their lives barely spared by a group of Crow Indians a few days prior. The Crows had let them go in order to keep other white folks out of their treaty-defined and legally-protected territory. The release of the Fairweather party would prove prophetic for the Crows. With the gold strike came settlers, miners, and eventually John Bozeman, whose trail would become the catalyst for a series of events that would formulate national Indian policy and create the first Crow agency, Fort Parker.

Bozeman began guiding folks along an old Indian passage which bypassed the Oregon Trail in Northern Wyoming. The Bozeman Trail was the match that lit the flame of Lakota ire. The Lakota Sioux had been displaced from their hunting grounds in the Dakota Territory and into the west around the Powder River. In the 1851 treaty signed at Fort Laramie, the Lakota were given the eastern side of the Powder River and the Crow were given the western side. The region was associated with the Crow Indians or Apsaàlooke, which the Crow called themselves. The Apsaàlooke wanted the Powder River Territory back and the U.S. Government representatives who came to negotiate with the Crow made many promises along that line.

The Lakota threat stopped traffic along the Bozeman Trail and the three forts built to secure the road, Fort C. F. Smith, Fort Phil Kearney and Fort Reno created even more anger and animosity. The Lakota tried to recruit the Crows into their ranks against non-Indian encroachment but the Crows played it neutral while they determined which side would best serve their interest. After many promises offering a return of the Powder River, the Crows decided to support the U. S. Government against their old rivals and enemies, the Lakota.

Back in Washington, the Indian Bureau could no longer tolerate the violence in the west which culminated in 1867 with the murder of John Bozeman. Ironically John Bozeman was killed near present day Mission Creek, along his famous trail. The Bureau formed the Peace Commission in order to treat with the Indians who offered the greatest threat. Their mission was peace at almost any cost. This “promise them anything” policy was the reason the Crow Indians lost the Powder River and ended up with an agency and reduced territory.

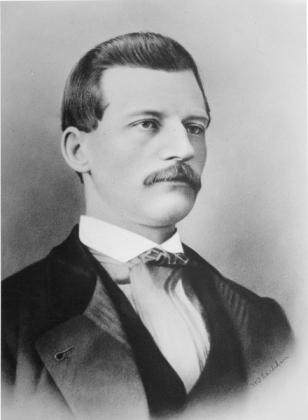

After a failed initial attempt at treaty-making with both the Sioux and the Crows in the fall of 1867, the Crows were brought to the table again in the spring of 1868. For an undetermined reason, the Crows arrived late to find that the Sioux had been given the Powder River with their promise to abandon the Bozeman Trail. The peaceful Crows, who had allied themselves with the U. S. Government lost 70 million acres of their territory for an annual receipt of goods and an agency for their distribution. This agency would come to be named Fort Parker after Eli S. Parker, the first Native American Commissioner of Indian Affairs.

Newly-elected President Ulysses S. Grant took office in 1869, the same year Fort Parker was built. As the atrocities of the west were becoming known in the east through pamphlets like the Report of the Condition of the Indian Tribes and Lydia Maria Child’s pamphlet “An Appeal for the Indians” which detailed the greed of Indian agents and the horrors of the Sand Creek Massacre, among others, Grant’s eastern constituents were demanding change in Indian policy. Grant reluctantly agreed and looked to religious organizations to deal with the Indian issue. The resulting “Peace Policy” evolved and played itself out at Fort Parker during the years 1869 – 1875.

Fort Parker was constructed under the authority of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the hand of Leander M. Black, a Bozeman businessman who gained the contract for construction. In May of 1869, Capt. E. M. Camp was assigned as Indian Agent for the Crows and in June left Washington D. C. to collect supplies on his way to the new Fort. His journey was lengthened due to low water on the Missouri which caused his steamboat, the Fanny Baker, to lay aground for two weeks.

In September, Alfred Sully, Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Montana Territory, chose the site for the agency with a group of Crow Indians who had remained behind for the fall buffalo hunt. The treaty located the agency near Otter Creek, but Sully felt the ever-attacking Lakota were too close to this location and the Crow were not happy with that area. Ultimately a site was chosen about 40 miles from the military base at Fort Ellis putting it near enough to be under its protection. The location was along Rock Creek which would come to be known as Mission Creek and the agency would come to be known to the Crows as the Mission. By November the fort was under construction and a ferry was established by William “Billy” Lee to bring provisions across the Yellowstone. The ferry crossed about seven miles from the fort on a creek that would come to be known as Ferry Creek.

The first crops at the fort were planted in the spring of 1870. Seven acres were plowed and planted with cereal, grains and vegetables. Reports from around the region tell of the scarcity of buffalo and the starvation of tribes. As treaties were trading goods for land, the Indians became dependent on the government goods for survival.

In August, Camp writes his first report noting that “The wheat, barley, and oats turned out moderately well. Late frosts in the spring and a heavy frost the beginning of this month killed the corn and such vegetables as beans, tomatoes, melons, and squashes, all of which were thriving well until the extraordinary visit of a frost in early August killed them.” He also recounts several violent encounters with the Lakota and notes, “While the Sioux Indians act beyond the control of the Government, and make raids with impunity on Indians . . . peaceably disposed toward the whites, and are permitted to invade their reservation in such numbers as threaten to drive the Crows out of it, I think it but proper in this case that the Crow Indians should be armed to defend their own homes, not for the purpose of fostering war between the Sioux and the Crows, but for a reason of policy.” Finally, he offers a clear description of Fort Parker “This agency consists of the following buildings, all in good order and repair, viz: Warehouse, agency building, houses for physician, engineer, blacksmith, carpenter, farmer, and miller, and a building to be used as a school-room. The agency building or “mission-house” is at present used as quarters for a sergeant and twelve men of Company A, Seventh United States Infantry, detailed as guard for protection of this post. There are two bastions on diagonal corners, in each of which is mounted a 12 pound howitzer.” Thus Camp’s first year as agent finds a crop failure and continued Lakota violence. Both events will continue to plague Fort Parker throughout its existence.

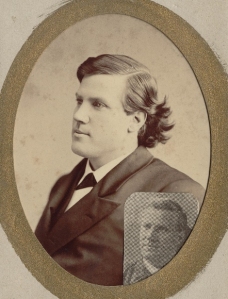

Due to a change in Indian policy which disallowed military employees to be Indian agents; Camp was replaced by Fellowes D. Pease, former trader with the Crows at Fort Union. Pease arrived at Fort Parker in January of 1870, a year that saw Grant’s Indian policy end treaty-making with Indians. The beginning of this year also saw the death of Isaac Newton Parker, brother of Indian Commissioner Eli S. Parker, who had been appointed as the first teacher at Fort Parker. In the spring Pease contracted with Bozeman business man, Charles Hoffman, an old friend from his Fort Union trading days, to build 20 adobe houses for the Crow Indians who indicate a desire to farm. Construction and inspection of the houses was concluded at the end of February.

In August of 1870, Pease offers his first report. He details concerns about the annuity goods, requesting more blankets and less flannel and extends the Crows concerns for the lack of treaty-promised cows and oxen. He also expresses great concern over the amount of white miners coming into Crow territory, which was expressly forbidden in the treaty. Because of this, he requested a survey of the territory to establish clear boundaries. He reported of continued hostilities by the Lakota and complained of the poor state of the agency buildings “None of these buildings are properly suited for the purposes for which they are used; all need repairing, all of them should be raised, and have a pine roof and pine shingles”

The new teacher, J. H. Aylesworth offered information concerning the school in his letter to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs in August of 1871. He reported that attendance had grown to 34 students, though their seasonal lifestyle, he noted, interferes greatly with the children’s education. He suggested that boarding the children away from their parents under the care of a school mistress, would render better results. He also requested an interpreter for the lessons.

The 1872 annuity distribution for the Crows took place in March. A fellow named “Slim Jim” gave a thorough description to the Bozeman Avant-Courier newspaper. He noted that Iron Bull, wearing a military uniform with epaulets, gave the opening oratory in Crow expounding the Indians to think of things spiritual and not temporal. Then the warehouse doors swung open and the writer described the large amount of goods offered to the Crows. “Bolts of calico, sheeting and ticking, piles of tobacco, sacks of sugar, coffee and four kegs of powder, and other things.” He then offered that the Indians present Major Bowen (acting agent while Pease was away), Charlie Hoffman (Sutler) and a Mr. Ferris with a “shower” of robes, followed by music and dancing by the Indians. Afterward, a group of Crow warriors on stolen Sioux horses, rode in a circle, singing of their exploits among the Lakota. At the close of this event, the crowd piled out of the Fort for an Indian horse race.

“Slim Jim’s” description of the distribution indicated a great appreciation of the Crow goods. Thomas Laforge, a white Fort Parker employee, adopted by the tribe offered a different view. Laforge notes, “The ‘annuity’ clothing which a benevolent Indian bureau at Washington sent out to the supposed naked and freezing savages on the Yellowstone was equivalent to seed sown upon bare ground. During the summer seasons, neither the Indian men nor their white-men companions in the hunting camps wore any clothing but the ever-present breech-cloth. When winter came they preferred the skin clothing, or merely wrapped themselves in buffalo-robes or blankets. As the wild animals began distinctly to decrease in numbers, the government apparel came gradually into use, with its ludicrous misfits. But in the earlier days, when Nature was bountiful, a pair of trousers or a pair of shoes could be bought from an Indian for twenty-five cents.”

In June of the same year, Superintendent Viall requests Pease to talk with the Crows about moving the agency to a better location. Indications had been that the poor farming and high winds at Fort Parker made it difficult for the Crows to farm. With another year’s crops destroyed by flooding and grasshoppers, clearly the site at Mission Creek was not going to obtain the intended results.

In August, a Northern Pacific Railroad survey team with 400 troops from Fort Ellis was attacked on the Yellowstone River by a group of 400 – 500 Indians. The survey party retreated to Fort Parker to regroup. There they met another military escort from Fort Ellis which enabled them to continue their work surveying a route for the coming Northern Pacific Railroad. The planned route would take the railroad directly through Fort Parker and the Crow Reservation and was another motivation to move the agency.

In his second report in September of 1872, Pease noted that the coming railroad and the continued encroachment by whites on their reservation had unsettled the Crow. Furthermore, he found that several key requisites of the treaty had yet to be fulfilled including the promised oxen and cattle as well as farming supplies and equipment. He indicated that the Head Men of the Crows were willing and anxious to relocate the agency and wished to meet the President in Washington, D. C., a trip which had been frequently promised in the past but had failed to materialize. He indicated that though the annuity distribution took place in February, the tobacco didn’t arrive until June and as the annuities were to be distributed in September, these goods were considerably late. With requests for needed supplies ignored as well as escalating threats by the Lakota, Arapahoe, and Cheyenne, Pease revealed his frustrations in the final statement of his report, “I have abstained from making many suggestions in regard to changes or future operations at this place, for the reason that my suggestions in last year’s report have received little or no attention.”

Back in Washington, Grant’s new Indian policy was evolving as he asked religious leaders to appoint a Board of Indian Commissioners whose uncompensated task would be to oversee the Indian agents and the distribution of annuities. Endorsed by Congress as part of the Indian Appropriation Act of 1870, the Board of Commissioners would hold authority over all expenditures for the Indians and advise and consult with the Commissioner of Indian Affairs as to all Indian-related concerns. The President of the Commission was Felix R. Brunot, a lay Episcopalian, whose perspective on Indian affairs was more of “civilization” than warfare. Brunot made a trip to Fort Parker in July of 1872 to meet and talk with the Crows about moving the agency to a new location. However, the Crows were unable to return to the agency for the meeting with Brunot due to a skirmish with another group of Indians. Brunot would return a year later to negotiate the final details of the agency’s re-location.

Escalating Lakota hostilities saw the deaths of several Fort Parker employees in September of 1872. A small party of Lakota killed Charlie Noyes and Max Jose while attempting to drive off horses from the agency. They were stopped by agency employees, including Tom Shane who shot and killed one of the raiders’ horses. A much larger party of Sioux attempted a raid at the end of September killing two Crow women, an infant, and Dr. Frost the agency physician. The agency butcher, Tom Kent, witnessed the murder and brought the bodies back to the agency for burial. The incident made a “deep and lasting impression” on Tom and may have led to his leaving the agency for a time.

On the night of October 30, 1872 the agency buildings caught fire. The Bozeman Avant-Courier reported that a former employee threw ashes on sawdust in the north bastion. The ashes caught fire during the night but were doused, inspected and believed to be extinguished. But at 2:00 am the north bastion was engulfed in flames and heavy winds spread the fire rapidly. The loss was total. Though no one was harmed, the heat of the fire caused the cannons to explode, making for an exciting spectacle.

Due to the urgency of oncoming winter, new agency buildings were under construction immediately following the fire. Adobe bricks replaced the former cottonwood logs as the primary construction material. Temporary housing and offices were set up in the 20 adobe houses, unoccupied since the Apsaàlooke were away for the winter.

The Spring and Summer of 1873 saw continued Indian hostilities. The daughter of Dr. Hunter, of Hunter’s Hot Springs resort just down the Valley from Fort Parker, describes several events that brought the family under the protection of Fort Parker, “the Sioux Indians were troublesome; they were seen on the highways to the Crow agency. They often chased employees at the Springs and watched their work in the fields, their signal fires burned at night and on mountains the flashes from mirrors were frequently seen as signals during the day, Pease, agent at the Crow Agency urged my father to bring the family in for a time.”

That summer also saw the building of a saloon at the Yellowstone ferry crossing by Dan Nailey and Amos Benson which would become the focus of social activity called Benson’s Landing. The proprietors coaxed the Indian trade with dances and liquor. Social events and activities were also encouraged among the workers at Fort Parker. Thomas Laforge describes the dancing that took place regularly. “Jim Hale, the violinist, was carried on the pay-roll as a mason, but his genuine service was that of promoting the dances. Barney Bravo beat the snare-drum, and a man named Ike Allen sometimes joined him with a tin pan used as a drum. The dances occurred once or twice a week, maybe three times. Mostly the program was of quadrilles, with occasionally a waltz or a polka.”

Moving the agency continued to be a topic of discussion in Congress. On March 3, 1873, the President approved House Bill 1282, an act authorizing negotiations with the Crow Tribe for the “surrender of their reservation or a part thereof.” A letter submitted by James Harlan, Chairman of the Senate Committee of Indian Affairs, offered the opinion of Superintendent Viall who had requested Pease to discuss the matter with the Apsaàlooke. Viall states, “the Crow tribe of Indians have indicated their desire to cede to the United States the whole or a portion of their reservation And are desirous of negotiating with that end in view.” No record has come to light of Pease’s discussion with the Crow Chiefs, so it is impossible to confirm whether this statement is a fair representation of their wishes. Reasons for reducing the reservation and moving the agency were several. The current location was not producing the farming results that were crucial to the reservation process. The Apsaàlooke themselves seemed ready to negotiate. They saw a dim future for the buffalo and they also needed support to fend off the Lakota. The recent fire also prompted the need for decisions. Finally, the Northern Pacific Railroad Expedition had charted a course directly through Crow territory. The fate of Crow Country was sealed and Felix Brunot, President of the Board of Indian Commissioners was again dispatched to carry out the negotiations at Fort Parker.

After a conference of the Commission at Fort Ellis, Brunot and a party consisting of General E. Whittlesey, of Washington DC, and Dr. James Wright left for Fort Parker to begin negotiations. The meetings occurred between July 31st and August 18 of 1873. Wright had been appointed Viall’s replacement as the Superintendent of Indian Affairs for Montana, just before a major administrative overhaul dissolved the position. Wright attended the negotiations as a member of the commission, but would stay on as the new agent for the Apsaàlooke, replacing Fellowes Pease, to the great regret of the Indians.

The negotiating party arrived at Fort Parker on the morning of July 30 to find that the majority of the Tribe had yet to return. They had been delayed again by a battle with the Lakota. This encounter, known as the Battle of Pryor Creek, had the Apsaàlooke along with forty lodges of Nez Perce, battling Crazy Horse and his band along Pryor and Fly Creeks. Both sides held firm with few casualties and the battle included a daring rescue of Crazy Horse.

A contingent of Crow Chiefs, including Sits in the Middle of the Land (aka Blackfoot) who played a significant role in the battle, must have left Pryor Creek immediately after the hostilities to meet with Brunot and party at Fort Parker. The Chiefs told them that the tribe would be delayed due to the battle. The conversation between Sits in the Middle of the Land and Brunot was recorded by Thomas K. Cree, Brunot’s secretary, and offers an interesting glimpse into the minds of these two important men coming to the negotiation table.

As the physical battle with the Lakota had come to an end, the mental battle between these two men began with each vying for their terms from the start. After a warm greeting by the Indians, Brunot asks how many days away the Tribe is. Sits in the Middle of the Land turns the tables to the Native reckoning of time when he responds, “We can’t tell how many nights; six or seven, perhaps.” Brunot, who had left Washington the first of June, Clearly wants it understood that he was kept waiting and ultimately missed the tribe on the previous year’s visit. This posturing by Brunot is a clear example of the disconnect between those in Washington holding the legislative reigns and the reality of Native life on the Plains. Battles, such as the one that delayed the Apsaàlooke, took place, not to win territory or power, but to win glory and esteem. They were significant to the social and political structure of the tribes which could not function without them. Brunot’s tone here suggests that he has little understanding of this system or of what had just taken place. It also shows a lack of understanding of the precarious situation playing out on the Plains at this time with the constant threat of warfare by the Lakota.

Perhaps Brunot began to understand better as Sits In the Middle of the Land told his story of the battle, making certain to emphasize that the Lakota seemed to be getting guns and ammunition from white men. “The Sioux must have good white men friends on the Platte and Missouri. They get guns and ammunition; they are better armed than we are . . . The Great Father does not know that the Sioux get these arms and ammunition, and then they kill white men with them. The Crows do not kill white men; the arms and ammunition we get is to hunt with, and defend ourselves and our white friends with.” The question as to whether to arm the Crows had been ongoing since Fort Parker opened its doors. Camp had requested arms for them in an early letter to Washington. It was clear that the administration of Fort Parker and even some of the residents of the Yellowstone Valley were looking to the Crows for protection against the Lakota. The Crows themselves knew that without equivalent resources, the sheer numbers of Lakota would eventually annihilate them. Supplying the Crows with arms was crucial to their survival. Thus Sits in the Middle of the Land makes a strong stand for them even before negotiations had begun.

The Crow Chief further explains to Brunot that in order to come in to negotiate, they had had to cut their buffalo hunt short, where they had intended to bring in skins for their lodges. He further explains that not all of the Apsaàlooke would be able to leave the camp due to the threat of the Lakota. He relates that they have every intention to remain loyal to the Great Father, but they want to fight the Lakota. “The Sioux want to get our country, but we will not let them have it” He tells them.

Brunot assures the chief that the Lakota are not getting guns from the Government and confirms the loyalty of the Apsaàlooke. He plays another angle by mentioning that the Utes and “nearly all the Indians are going to do as the President wishes them.” He suggests that the President will send the military after the Lakota if they don’t get in line “but he does not think the Crows want any soldiers for they are his friends and will do what’s right.” He is clearly setting a strong, if not threatening, tone for the negotiations.

After some discussion of cattle grazing, Brunot asks “Where is the best country you know of for Indians to live on?” Sits in the Middle of the Land senses Brunot pushing the discussion and clearly is not ready to tip his hand just yet. ”I am going to tell you, but we are not ready yet. We have land we like very much, and we will tell you about it when our people come in.” Brunot tries to push the question again and Sits in the Middle of the Land cautions him. “Do not be too fast; wait till all are here. When the rest come in we will tell you our mind.” The chiefs agree to stay for dinner then to return to bring in the camp. Both sides got a preview of the negotiations to come and clearly drew their lines in the sand.

The reality of the battle came to light when the Indians arrived on August 8. Several had died on the way to the agency and Chief Long Horse was in mourning for the loss of his brother who had been killed in the battle. Both Sits in the Middle of the Land and Iron Bull, the two principal chiefs for the tribe, were ill. Negotiations were postponed for several days until the chiefs regained their strength.

The intended outcome of these talks, as far as the Government was concerned, was to reduce the reservation from roughly six million acres to roughly three million acres and to relocate the agency buildings somewhere in the Judith Basin, south of the Missouri River. In his book The Great Divide, The Earl of Dunraven, who happened to be at Fort Parker during these negotiations, describes the Judith Basin as “a land certainly not flowing with milk and honey, not even with milk and water, or water alone.”

Though the negotiations promised to give the country to the Apsaàlooke alone, all knew the ridiculousness of trying to keep other Tribes, as well as the steady stream of settlers, from entering the territory. “However,” Dunraven continues, “when Uncle Sam ‘requests’ a small tribe to exchange their reservation, it is much the same as when Policeman X 220 ‘requests’ an obstructionist to move on. After a little remonstrance the tribe, like the individual, sees the force of the argument and accedes to the request.” So the Apsaàlooke reluctantly agreed while expressing their concerns which included the protection of their territory, the retention of Pease as their agent (they would lose) and arms against the Lakota (they would eventually win, though it would take some additional pushing).

After much discussion and oration, including some passionate speeches by both Sits in the Middle of the Land and Iron Bull, an agreement was signed on August 16th which relinquished their current reservation for a smaller territory and a new agency in the Judith Basin. The agreement also included one million dollars to be put in trust for the benefit of the Indians to be held in perpetuity with the interest “expanded or reinvested at the discretion of the President for the benefit of said tribe.” The agreement dissolved the 1869 Treaty of Laramie and relinquished right, title and claim to the previous reservation. Finally the agreement included a stipulation for the government to punish any poisoning of wolves in the territory, a practice anathema to the Indians, it was initiated by white trappers in order to protect the fur from damage during killing. The agreement was signed by every Crow member present.

Based on his understanding of the history of such agreements with the United States, The Earl of Dunraven wrote this about the treaty: “The Crow tribe will not, in all probability, cumber the earth for many generations; and the one million dollars, held for their use in perpetuity, are likely to revert to Uncle Sam before very long; but in the meantime, the adhesiveness of the material used in paying Indian annuities being proverbial, it would be interesting to know how much of the interest will fall into the Crows’ hands and how much will stick on the way.” His cynicism continues as he goes on to eloquently point out that “In fact, the value of the whole new treaty does not amount to that of a row of pins, for the fulfillment of it depends entirely upon whether anything of value is discovered on the new reserve, in which case the Absaraka will be again ‘requested’ to take up their beds and walk. No one can appreciate this more fully than the Indians themselves, who have learned by hard experience the true value of such treaty obligations. No people can feel more keenly the pain of parting from their old hunting grounds, from the burial places of their fathers and the birthplaces of their sons.”

The Judith Basin agency, however, was never meant to be. Prominent citizens of the newly formed town of Carroll, Montana protested the reservation which would separate them from the new capital at Helena. These cries eventually made their way to Washington where the agreement failed to be ratified. Later a new location would be chosen along the Stillwater River, which would put the Apsaàlooke directly on the front lines in the ongoing battle with the Lakota.

During the negotiations and to the great chagrin of the Crows, Fellowes Pease was replaced as agent by The Reverend Dr. Wright, the former Montana Superintendent and Commissioner at the negotiations with Brunot. Dr. Wright was a Methodist Episcopalian Minister and his appointment clearly indicated Grant’s “Peace Policy” of choosing high-minded men endorsed by the churches. Though loved by the Crows, Pease did not have the religious clout that Grant’s policy required and had made no strong attempts at “Christianizing” or curbing their traditional ways. Wright had the religious zeal necessary to enforce the required change. One of his first actions was to organize a temperance society of Good Templars at the agency which grew from 15 members at its inception in October of 1873 to 24 members in September of 1874.

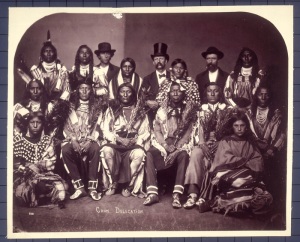

Pease wasn’t out for the count, however. The Apsaàlooke had made their feelings for him very clear at the negotiations. Any attempt to extricate him from their society would certainly be cause for alarm. He was given a series of significant duties to aid the Crows in the process of moving their agency. Besides leading the expedition to the Judith Basin to search for a site, he would also lead a delegation of Crow Chiefs and their wives to Washington D. C. to meet with the President. He had suggested the idea back in his first report as agent, noting that “These Indians are anxious, before making any further treaty, to go and see their Great Father at Washington, and have a talk with him personally, as they think any promises made by him to them will be more faithfully observed.” With the conclusion of the negotiations, a trip to Washington, Pease and the Apsaàlooke thought, would seal the deal and confirm the Tribe’s needs as defined in the agreement.

“A delegation of Chiefs of Mountain Crow Indians left Bozeman yesterday morning for Washington in charge of Major F.D. Pease, on a visit to the President. We doubt if a finer body of Indians ever visited the Great Father before. They are fine-looking, remarkably intelligent, and have always been true friends of the whites. Blackfoot and Iron bull are the most prominent chiefs in this party. We bespeak for these noble red men a kind reception and hope that the President and Indian Department will be liberal and generous to them, for these Crows have conducted themselves towards the whites in this section much better than Indians generally do on the border.” With this glowing sendoff in the Bozeman Avant Courier, a delegation of Crow chiefs, their wives, Fellowes Pease and several interpreters left the Mission Agency for Washington D. C. The delegation met with Secretary of State Columbus Delano on October 21st and expressed their disapproval of the terms of the new agreement and territory. “One of the chiefs said that the government had given them for their country a tract of land on which there is no wood, water or grass; nothing but rocks, and his people could not raise corn to eat,” noted the Washington Herald. Later, the delegation managed a trip to New York on November 1st, 1873, where the New York Times noted they stayed at the Grand Central Hotel. While in Washington, Pease met with the President of the Northern Pacific Railroad who indicated that plans were underway to begin laying track to the Yellowstone by the following season. Such news came as cause for great relief to the Bozeman residents who laid the future economy of eastern Montana at the feet of the railroad.

Pease returned to Fort Parker with the delegation on December 12. The success of impressing the Crows with the great white civilization of the east was imagined in the Bozeman Avant Courier. “Our Eastern exchanges represent the Crows as the finest body of Indians that has ever visited Washington, and the Chiefs returned to their tribe with their ideas considerably magnified in regard to the greatness of the pale faces and the extent of our civilization. Being their first visit to the Eastern cities, they possess an inexhaustible fund of gossip, which they will spin out over the camp fires this winter to their astonished squaws and less favored brothers of the breech-clout.”

While the delegation was back east, newly appointed agent Wright wasted no time in setting about on his task to Christianize the Indians. He opened a school at Fort Parker on October 27 and asked all of the non-Indian employees to contribute at least five dollars to the school and church fund. Agency employee Thomas Laforge noted that the school was not as popular as the church because the teacher required the children to cut their hair, a sign of mourning to the Crows. This cultural ignorance would be carried on with Richard Henry Pratt’s boarding school system, established in 1879, whose motto was “Kill the Indian, Save the Man.” Later, Crow children would attend Pratt’s Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania where their Indian identities would often be beaten out of them. The legacies of such abuses are felt on Indian reservations today.

The school was just the beginning for Wright, however. Regular lectures were offered in the established Lyceum, a newspaper called “Our Paper” kept everyone up on local events and regular church services and a Sunday school were offered with preaching from such prominent Bozeman ministers as the Reverends T. C. Iliff and W. W. Alderson. An organ arrived in December of 1873, noted George Ingram in a letter to the Editor of the Avant Courier,“there is no other persuasion needed to get the boys to attend singing on the Sabbath evenings than the excellent music drawn from it by one of our amateur performers.” Thomas Laforge notes that “Little ones wearing only a breech-cloth, would sit with chins in hands and listen rapturously to the unpolished harmonies.”

Holidays were celebrated with all the pomp and circumstance that could be mustered with limited resources. Thanksgiving of 1873 was no exception. George Ingram wrote a description for the Bozeman Avant Courier “The 27th was a beautiful day for the time of year. A general order was given by the Agent that no work should be done, and for everyone to enjoy himself as best he could. At 12 pm. the bell (alias triangle) sounded for Divine Service. We all gathered in the school house, and after Dr. Wright’s reading the Governor’s proclamation, we were treated to an excellent sermon by Mr. Iliff. About 3 o’clock the bell was brought into requisition again – to call us to the dining room to partake of a dinner, the equal of which has never been seen on the Yellowstone. In fact, it was as near an old fashioned Thanksgiving dinner as it were possible to get at in this country. Although the proverbial turkey was not on hand, we had a good substitute – about two dozen grain fed prairie chickens, and the tables were replete with pumpkin and mince pies and other things too numerous to mention. In the evening we congregated in the schoolhouse for evening service, which consisted of singing, prayers and short discourses from the reverend gentlemen present, closing with a great little song by Mrs. Iliff, entitled “My Trundle Bed” which in fancy carried us back to our childhood home and the many Thanksgivings we had spent there.”

After his return from Washington, Major Pease was appointed Special Indian Agent and led an expedition to find a location for the new agency in the Judith Basin. He was accompanied by Lieutenant Doane and a cavalry escort from Fort Ellis. A letter to the editor of the Bozeman Avant Courier from the expedition paints a very different picture than the reports of both the Crows and the Earl of Dunraven. “If the Brunot treaty is ratified the Indians will here get a fine country and if they are ever induced to give up their roving life and engage in farming and stock raising, no better portion of Montana could be set aside for them, while the Boundaries of the new reservation are such that no white settlements can be formed near them.” The writer’s sentiments seem to belie reports earlier that same year of eager settlers moving into the area “The Yellowstone Valley is fast settling up. The largest settlements being some 35 miles from Bozeman. So soon as the Crows are removed from their present reservation all that beautiful and rich country will be filled up with a large population. Parties are waiting with anxiety for that event to secure the best lands,” Reported the Avant Courier in April, 1873. The rapidly advancing settlement was just a part of the problem with the Judith Basin. The area was common hunting ground for several Indian tribes, including the Sioux and trying to keep them out would prove impossible. Miners, too, were roaming the basin looking for gold and silver while the ever anticipated Northern Pacific would leave them on the wrong side of the tracks, separated from the larger buffalo herds to the south. The Crow were not happy with this arrangement.

Their sentiments against the Judith Basin were shared by a surprising source but for a very different reason. In May of 1874, Lt. Gustavus Doane, who accompanied Pease on the expedition to the Judith Basin, established a steamboat landing at the Missouri River terminus of the Fort Ellis-Carroll Wagon Road. This landing was to become the “up and coming” town of Carroll. Helena merchants were also interested in this new access to eastern goods being shipped along the Missouri River. The anticipation of the growth of this new town made Helena merchants and politicians concerned about the Judith Basin location for the new Crow territory. The reservation would separate the growing town of Carroll from Helena, its financial wellspring. Also, the established trail for moving goods from the steamboat landing to Helena would pass right through the reservation. Political strings were pulled and the treaty with the Crows to trade their reservation for land in the Judith Basin was never ratified. A new location for the agency would be required.

Many of the white agency employees at Fort Parker married Crow women. Often it was for access to land allotted them. If the men were traders, it would also insure that their merchandise wouldn’t be tampered with by Indians. Occasionally, however, they married for love. Thomas Laforge tells of his courtship and marriage to Bah-te-chua (The Cherry). “Cherry, a tall and attractive Crow girl, became to me unusually interesting. She had brown hair, hazel eyes, evidently was of mixed race, although I never did learn the source of her white blood. I conceived a special liking – or perhaps it was a deliberate cultivation of liking – for her brother whose name was Head-and-Tail Robe. I visited often with him at their tepee lodge. During these visits I never spoke directly to the girl. Yet, by means of the mysterious telepathy that flashes between congenial spirits, I came to know that she preferred me above all other young men. Her mother, a widow, evidently got an intuitive knowledge of the situation, and one day, in their lodge, she began berating me on account of my unkempt personal appearance.

“Oh, your ragged moccasins!” she derided. “You ought to have a wife, some one who would keep you supplied with good clothing and who would keep your long and curly hair well oiled and well combed.” Pretty soon she continued: “Cherry can make good clothing. I’ll have her make you a coat and some good moccasins.

“But he ought to have a white wife to make his clothing,” the girl protested. “He would not want an Indian woman.

“They went on in further dispute, or in affectation of dispute, on this question. I did not commit myself. But the talk fixed my mind upon the matter. I was twenty years old and was growing a budding mustache. Cherry was eighteen. I was sure I loved her – no doubt about it then or ever afterward. I determined then and there to defy convention, to turn my back upon the deprecating white people, to have an Indian wife, to be altogether an Indian in mode of life.

I took some canned goods the next day and set them inside the entrance to their tepee. On succeeding days, and in the same Indian fashion followed in making presents, I gave them some blankets, calico, sugar, coffee, bacon, beads – lots of beads. Each time I merely opened the tepee flap, set in the presents, and went away.

“Mitch Buoyer’s wife took an interest in the affair. “Cherry is a good girl, on of the best in the tribe,” she assured me over and over. One day I authorized her to tell my adored one I wanted her for my wife.

“Cherry came the next day to the doorway of my blacksmith shop. She stood there a few moments, smiling, then she sat down on her blanket spread upon the ground outside. How agitated I was! What calm and self-control she exhibited! I went out pretty soon ans struck up a conversation with her. Although I was not bashful,– in fact, quite the contrary, — I was embarrassed and shaky just then. I stammered out an inquiry if she had a good awl for sewing. No, she hadn’t any such tool. I jumped to the work and made her two good ones. After a while she went away.

“Late that afternoon I saw Cherry and her sister-in-law pass along the road, each of them carrying on her back a bundle. They went to Mitch Buoyer’s house. As I was about to close shop for the day Mitch’s wife called to me:

”Somebody at our house wants to see you, Tom.”

I found a big room that had not been in use transformed into a homelike place. My little personal effects were combined there with those of Cherry’s lodge. She had made up my bed in the best form it had presented for many months. That was her token of marital intent. From that day on we were husband and wife, by virtue of mutual consent. We remained so throughout many years, until we were parted by death.”

The Reverend Wright was not fond of these “unmarried” couples, as he saw them, and required all white men “cohabitating” with Indian women to marry. A mass marriage ceremony was conducted on Jan 9, 1874 in which Tom and Cherry were married in a Christian ceremony, though they had been married in their own eyes for many years. They had a son named Tom Jr. Cherry would not survive the year. Her death was reported in the Avant Courier on September 6, 1874.

Later that same year the agency butcher Tom Kent married “What She Has is Well Known” who came to be known as Mary. Tom paid five head of fine horses, guns, ammunition, blankets and more to Mary’s uncle “Poor Elk” who had raised her as his own child. Because of this bride-price, Mary was considered a queen among women. She lived with Tom and his mother on a ranch near Bridger Creek and after Tom died, continued to live with her mother-in-law, who loved her more than her own daughters, until the mother-in-law died ten years later.

The agency school was growing under Wright’s tenure. The Reverend Matthew Byrd of Bozeman was appointed minister and teacher at Fort Parker in the spring of 1874, replacing Aylesworth who left after Wright had replaced Pease. Pluma and Mary Noteware were school mistresses and their mother Ruth was matron of the boarding house. They cared for the children who were boarding and made clothing for them. The Avant Courier reported on the school in December of 1873. “Mrs. Noteware, a very estimable lady, is employed in making entire suits of comfortable clothing for the Indian boys and girls.

She has quite a number of them dressed in a respectable manner, and who are put under her supervision to see placed before them good wholesome food, etc. She sees them off to school week days, clean and neat, and also accompanies them to Sunday school, in which they appear to take great delight. We have a schoolhouse which answers a good purpose for various important exercises. It is a room well furnished, not the least among which is a well-toned organ, a delightful source of pleasure to us all. A common school is taught by a good, competent teacher, with splendid results. Also an excellent Sunday School, of which Dr. Wright is superintendent.” The school had 8 children, though one girl was stolen by friends. Wright notes in a letter to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs “There are some white children that attend. Used to have 20 Indians at a time. The Indians come in and get their rations and go away, and besides this, since we have dressed some of their children as whites dress, the children wearing Indian costumes do not like to attend regularly.”

The Sioux threat was ever increasing and skirmishes were regular around the agency. Col. Baker and a contingent of men met them in battle along Pryor Creek in the Spring of 1874. Concern for the agency employees and their families prompted General Switzer to detail twenty five men from Fort Ellis to remain at Fort Parker, under the command of Lieutenant Long while Baker led his men into battle. Agency employee Thomas Laforge was involved in this battle noting that men were killed on both sides, including a man named Peeples who fought along side of him.

Because of this ongoing threat, Governor Potts again broached the question of arming the Crows. On June 24, 1874, he wrote to the acting Secretary of State, B. Cowen that “The Mountain Crows should be supplied on their reservation as they are scarcely absent from it and every inducement should be offered to keep them there. I would suggest to supply the Crows (Mountain) with authorization at or near their agency for their annual fall hunt and for the protection of their reservation from the encroachment of other Indians. I do not believe a day passes that the Sioux Indians are not in some force on the Crow Reservation and twice since I have been in Montana they have attacked their Agency and stole stock and killed their people on the very upper border of their reservation. The Flatheads and Blackfeet almost every year steal their horses…The Mountains Crows are entitled to the thanks of our people for their loyal defense of our eastern settlements and so far as I can I shall aid them for the protection they have afforded our people.”

As if to reinforce his point, the Sioux raided horses on the agency on the morning of July 1, just a week after Potts’ request. The Crows were off hunting between the Yellowstone and the Judith Basin and their absence had invited the Sioux. The Avant Courier reported “eight Indians made their appearance near Benson’s place, and run off six horses belonging to various parties. They fired six shots at George Town, a herder, none of which, however, took effect. About 10 o’clock a courier arrived at Benson’s from the Crow Agency, bringing the intelligence that about one hundred Sioux had come to the Agency and made signs for the occupants to come out and fight them. They did not succeed in getting away with anything from the Agency. It was impossible to estimate the number of Indians in the vicinity. They could be seen all day in the canyons. It would be well for the people of this valley to be on their guard and anticipate any raid that may be contemplated by the Indians. The leading pass into the valley is well guarded by troops from Fort Ellis, and our people will be notified of any such design, but it is good policy to be always prepared. The expedition of General Custer to the Black Hills will undoubtedly force the Indians this way, and the military force at Fort Ellis should be increased so as to meet any emergency that may occur.” The Sioux raided again a few weeks later capturing and killing all of the agency work cattle. One of the herders was shot in the arm and then killed with arrows. Another herder arrived at the agency unharmed but badly shaken.

Dr. Hunter brought his family to the agency for protection in July writing to the Editor of the Courier, “I am here. The Sioux have just jumped me up at my ranch. We exchanged shots – 5 in number. They got my horses and left. Eleven Sioux mounted on as fine horses as I ever saw. All I regret is that Gov. Potts was not with me, that he could have realized that the Sioux are in the country. It is thought that Dunphy’s Herder is killed; at last accounts about 40 Indians were in full chase after him and not far behind.” The Hunter’s home was looted while the family was at the agency.

Agent Wright’s assistant Captain Robert Cross spoke to Governor Potts of these recent Indian hostilities, speculating that some of these Indians may be Crows trying to oust Wright as agent. Potts wrote in a letter to Secretary Delano, “I would not be surprised if this theory is not correct for there is an intense feeling against the agent in the Crow Camp and this may have been adopted to frighten the agent away. The Indians made no effort to kill anybody although many opportunities were offered, I think Agent Wright is tired of the annoyance and has telegraphed Dr. Eddy and asked to be relieved.”

Wright’s ability as agent was not only questioned by the Crows, some Bozeman businessmen and citizens were also growing in their concern for Wright’s fiscal management of the agency. The Bozeman Grange met on September 18, 1874 to discuss questions concerning the disbursement of Government contracts and appropriations by the Agent. They chose to recommend to the County Council that two members of the Grange would report on the amount of beef, flour and pork issued to the Indians per month and that the Council would forward that report to both the Commissioner of Indian Affairs and to the Montana Territorial delegate to Congress, Major Maginnis. These measures were requested “to expose the corrupt management of Indian affairs by the present agent at the Crow Agency.” It was believed by those attending the meeting that the Crows had not been treated fairly by the agent, which resulted in their absence from the agency and an increase in Sioux hostilities. “It is a conceded fact that the tribe of Crow Indians are worth a regiment of troops to the Gallatin valley, while they are on their Reservation no raids are made by hostile Indians, and the settlers feel safe and secure, but during their absence the Sioux and Arapahoes come up the Yellowstone, cross through the different passes into the valley, drive off our stock and murder our citizens.” Reported the Avant Courier on statements made at the meeting. The Crows, “complain, and very justly too, that the small amount given them is not worth coming in for, and that they will remain in the buffalo country where they can get provisions for their women and children.” Finally, it was noted that “Last year the United States government appropriated one hundred and thirty thousand dollars for the Crows, and we will venture to say that not one-fourth of the amount was expended for their benefit.”

The members of the Bozeman Grange sensed fraud and corruption at the agency under Wright’s leadership and with good reason. The Reverend James Wright had found himself in the middle of a real “Indian Ring” – a term coined for fraudulent agents and suppliers working together to defraud the government. Wright had taken control of the agency with the best of intentions, hoping to Christianize and civilize the Indians, as he was instructed to do. Pressures, however, began to sway him from his appointed task. Certain Bozeman merchants saw the Government appropriation gravy train and had started taking advantage of the agency warehouse filled to the brim with goods. Wright’s own wife was on the take, wanting to retire in comfort back east. Under such pressure Wright succumbed. An 1878 investigation into a later agent of the Crows brought all the agency corruption at Fort Parker to light. Midnight loads of Government goods were freighted to a trading post in the Judith Basin to be sold to trappers and traders. Horace Countryman, in his deposition for the investigation, noted that food and supplies meant for the River Crows in the Judith Basin never found their way to the destitute Crows but wound up in the stores at the Judith Basin trading post. Countryman was able to persuade some of the River Crow chiefs to come to the trading post to receive their goods, which had been previously refused them. Countryman sensed real anger from the Crows which he felt could have resulted in violence. Many other examples of fraud and corruption are discussed in the 1876 report by James Brisbin to General Sheridan including under- supplying beef, pork and flour, selling government-supplied ammunition, theft of agency cattle and intimidating those who would testify before a grand jury. The members of the Bozeman Grange had good reason to wonder where all that money had ended up.

Whether it was the pressures of the “Indian Ring” or the threat of the Indians, Agent Wright reached his limit and resigned his post for a transfer to Fort Hall in October of 1874. He was immediately replaced by Dexter E. Clapp.

Wright’s hurried resignation came just as he was to see one success of his administration. Secretary of State Delano, finally granted permission to arm five hundred Crows for the purpose of protecting the Gallatin and Yellowstone Valleys from the Sioux. Wright would not escape clean, however, affidavits charging him with improper conduct were filed in May, 1875.

Clapp arrived with his wife in November and immediately made his connections with the Bozeman businessmen who would be freighting and furnishing goods to the agency. While he settled in, a new site for the agency was already being discussed and a expedition to find a new site left Fort Parker in December. Though the previous agreement to swap the current Crow reservation with one in the Judith Basin had fallen through, the pressures that caused that agreement were still at hand, particularly the anticipated railroad route which was planned to run straight through the reservation. A decision was made to relocate the agency on the Stillwater River and exchange a large portion of the Crow reserve for promised money and goods. The Avant Courier reported that the Crows were seldom on their reserve on account of the Sioux and suggested that an agency further down the Yellowstone would be more to their liking. Ironically, this location would put them directly in the path of the Sioux. Later it was reported that the move to the Stillwater would force the Sioux into a smaller range, keeping them further from the burgeoning Valley’s to the west. The former lands of the Crows were immediately opened up to settlement.

A site for the new agency was found and orders to move the agency came from the State Department in February of 1875. Work began immediately clearing the site and freighting in building materials and supplies. Work progressed rapidly and the new agency buildings were up and ready by April. On May 22, the agency employees packed up the remaining goods and materials and made the final move to the Stillwater, leaving the buildings of Fort Parker empty and abandoned.

They would not remain empty, however, a family named Hicks would settle in them and remain for several years. “The land on which that old stone foundation stands was the homestead of a man named Hicks. He and his family lived in the old adobe agency buildings, and when the country was surveyed, he homesteaded the land.” Reported the Livingston Enterprise, on October 17, 1957. Roll Fifield recalls attending dances hosted by the Hicks family at the old Agency Buildings. An Englishman named Kennelly made a deal to purchase the land from Hicks and began to build a “castle” a few yards from the agency buildings. The deal fell through, however, and Hicks refused to sell to him. The “castle was never finished and the ruins remain on the site today. The years took a toll on the old adobe agency and all that remains are the foundations of the second building, constructed after the fire of 1872. To the casual observer, they are barely visible on the ground of a quiet peace of grazing land. But what a story they have to tell!

We have been working closely with the Archaeological Conservancy to purchase the site of Fort Parker, the first Crow Indian Agency, for preservation and education. See our work on Fort Parker under “Projects” above. If you would like to contribute to this important preservation project, you can donate online at https://donate.archaeologicalconservancy.org/ Choose Fort Parker on the drop down menu next to “Designation” and all of your contribution will go towards this project. Thank you for your support!

December 5, 2013 at 8:25 pm

There is mention by Thomas Laforge of Mitch Buoyers’ wife, would this be Margaret Wallace? Didn’t Margaret Wallace later marry F.D. Pease after Buoyer was killed at the Little Bighorn Battle?

December 11, 2013 at 4:11 pm

Thanks for your question, Robbin. Mitch Buoyer was married to Margaret Wallace. They were legally married around 1852, though they had 3 children together who were born in the 1830s. They divorced, though, and Margarite went on to marry Fellowes Pease in 1860 at Fort Berthold, long before Buoyer was killed at the Little Big Horn Battle. She was also divorced from Major Pease before he took over as agent at Fort Parker in 1870.

January 12, 2014 at 5:57 am

Does anyone know Margaret’s actual Crow name?

January 12, 2014 at 10:07 pm

That’s a good question, Carolyn. We will check our research and see if we have it somewhere.

January 14, 2014 at 3:37 am

Any info you can contribute will be so appreciated. Thank you!

May 16, 2015 at 2:22 am

Wasn’t John Wallace also half French? 1900 census says half white….father was born in Ohio…later census.

May 19, 2015 at 5:51 pm

That is certainly very possible, Mary Ann. We don’t know much about him. Thanks for letting us know.

May 31, 2015 at 11:54 pm

My Mother Sarah Pease told me Marguerites name was Kills The One Who Herds The Horses but I don’t know how accurate that is.

June 1, 2015 at 11:38 pm

I was told a story that 2 children of Margaret’s were kidnapped by Sioux and she told F D Pease that if he brought them back to her she would marry him. He found the children and brought them back and she married him. Have you heard anything about this?

June 3, 2015 at 10:53 pm

That’s a great story. There is a similar story about Margaret and her brother when they were children. I can’t remember all of the details, but we have it in an oral history. I believe Margaret’s parents were killed by Sioux and that Her and her brother were left to fend for themselves. I will have to check on the details of that one. We haven’t heard this story with Pease, though. I wonder if the two stories are related. Thanks for sharing!

June 23, 2018 at 3:55 am

This is all very fascinating. My Great Great Grandmother was Margerette Wallace Cooper. I was reading about Fort Parker, which connected her to F. D Pease (2nd husband) and Mitch Bouyer (1st husband) Her third husband, my Great Great Grandfather James B Cooper had a amazing story as well. His death certificate stated that he married Margarette at Fort Stevenson in Dakota Territories 1869.

Margarette’s parents were John Wallace and I believe “Medicine that Shows” her brothers were Richard (1866) and John Wallace. I’m not sure how their mother passed but John Wallace (father) was killed by Sioux while traveling with his sons on a river boat down the Missouri River. Richard and John were cared for by the Hidatsa before being returned to the Crow.

Interesting side note. A Richard Wallace alongside other very prominent members of the Crow tribe took part in the 1920 negotiations between the Crow and the Federal Government. It would be interesting if they are the same.

June 25, 2018 at 2:08 pm

Wonderful family history, thanks for sharing!

April 17, 2019 at 4:10 am

Great grandfather so many times removed is Thomas LaForge, somewhere along the line, my 2nd great grandmother would have been Amy LaForge. However, I am missing a few great great..great grandparents. I know Amy’s father would have been Francis, but am unable to find out who his mother is. We know she was Crow, but he appears to have married at least three Crow women and from what is passed down verbally from my family, had roughly 19 children (unsure exactly how many survived to adulthood). Does anyone have any idea who Francis (Frank’s) mother may have been?